The field of long COVID research reached a major milestone last [month] with the release of a new report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) outlining a working definition of the disease.

This definition report, drawing from hundreds of scientific papers and the lived experience of people with long COVID, recognizes the disease as complex with “profound consequences” and clearly connects it to similar chronic diseases that can develop after infection. NASEM also published a second report, earlier in June, that describes how long COVID can impact people’s ability to work, attend school, or perform other day-to-day activities.

While thousands of scientific papers have previously described long COVID, the two new reports provide a higher level of authority due to NASEM’s rigorous research process and status among scientists and clinicians. Federal, state, and local government agencies, as well as research institutions, are likely to use these reports to inform their long COVID programs. A similar report about Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME) or chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), published a decade ago, was a milestone in recognizing the disease.

NASEM “really helps bring credibility to the information that we’ve gathered” in summarizing four years of research on long COVID, said Karyn Bishof, president and founder of the COVID-19 Longhauler Advocacy Project and one of the definition report’s authors. However: “Patients are still going to face the same issues,” such as dismissal from doctors, if agencies don’t adopt the new definition “from the top down,” she said.

In the days since both reports were published, many people with long COVID and researchers studying the disease have praised the NASEM committees’ work in recognizing the damage long COVID can cause. But others say the reports fail to direct appropriate attention to certain communities and issues within the long COVID space, including children with long COVID, those with the most severe symptoms, and people whose symptoms started following vaccination.

The definition report is “an important step” in recognizing long COVID, said Dr. Ian Simon, director of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Long COVID Research and Practice, in a statement to The Sick Times. HHS is reviewing NASEM’s proposed definition and recommendations; in the meantime, he urges people with long COVID to use the report in their own advocacy. “I would encourage advocates to continue to share their stories, educate us on the gaps they see in policy, the barriers they are encountering in finding treatment, and help us remain responsive to their needs,” he said.

Key findings from both reports

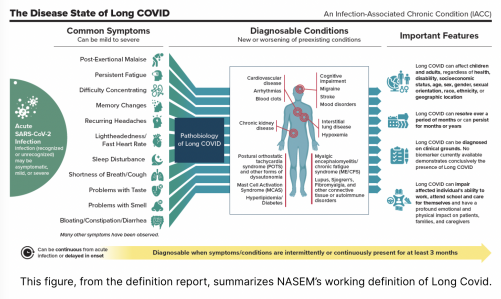

- NASEM uses the patient-developed term “long COVID” as opposed to other medical terms for the disease. It also defines long COVID as an “infection-associated chronic condition (IACC),” aligning it with similar diseases like ME/CFS, dysautonomia, and chronic Lyme disease and with the work of another NASEM committee about this group of diseases.

- With NASEM’s definition, long COVID symptoms must be present for at least three months “as a continuous, relapsing and remitting, or progressive disease state.” However, the report emphasizes that doctors do not need to wait three months to begin monitoring patients or prescribing potential treatments to alleviate symptoms.

- The definition includes a wide range of symptoms covering all parts of the body, as well as different conditions that may be diagnosed alongside long COVID, including cardiovascular disease, cognitive impairment, blood clots, chronic kidney disease, forms of dysautonomia, ME/CFS, mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS), connective tissue diseases, and autoimmune diseases.

- Long COVID can occur after any type of SARS-CoV-2 infection, from asymptomatic to severe. This definition also emphasizes that a positive SARS-CoV-2 test is not a requirement for diagnosing the disease, due to limited availability of tests and accuracy concerns.

- As no biomarkers for long COVID are currently available, the definition recommends that clinicians and researchers diagnose the disease based on symptoms. It provides many examples of potential symptoms but does not require any one symptom for diagnosis, aiming to include all people who are struggling with new or worsened health issues following a COVID-19 case.

- Long COVID can “persist for months to years,” the definition recognizes, and can “impair individuals’ ability to work, attend school, take care of family, and care for themselves.”

- The report makes it clear that long COVID can affect people of all demographics — and that people from already marginalized groups are especially vulnerable to the disease — and recommends prioritizing health equity in future research and healthcare programs.

- The disability report recognizes long COVID as a complex, chronic disease and finds it “can result in the inability to return to work (or school for children and adolescents), poor quality of life, diminished ability to perform activities of daily living, and decreased physical and cognitive function.”

- Health issues common with long COVID that can significantly impact quality of life, such as post-exertional malaise and autonomic dysfunction, are not included by the Social Security Administration (SSA) in its list of conditions that may qualify someone for disability benefits. The report describes many potentially debilitating symptoms and identifies which are and aren’t included on SSA’s list.

- Recovery from long COVID can be widely variable, the report finds. Some people find symptoms improve within a year of acute infection, while others may see symptoms plateau at this point. More long-term research following the one-year mark is needed, the report suggests.

- Children can get long COVID, leading to disruptions in school, social life, and other activities. Based on relatively limited data, the report claims the “trajectory for recovery” may be “better among children” than among adults, but notes more research is needed to understand the long-term challenges that children with long COVID face. Some advocates for children with long COVID dispute the recovery claim.

- Like the definition report, the disability report highlights health disparities, noting that people assigned female at birth, racial and ethnic minorities, LGBTQ+ people, those disabled before getting COVID-19, and other groups are at a higher risk for long COVID.

The HHS — specifically the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response and the Office of Assistant Secretary for Health — requested the working definition report, while the Social Security Administration (SSA) requested the report that examines long COVID as a disability, following news reports that people with long COVID were struggling to receive disability benefits from the agency.

Developing a NASEM report is “a unique process” that includes extensive review of scientific literature and lived experience, said Lily Chu, vice president of the International Association for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and an author of the definition report. Chu also served on the committee for a 2015 report defining ME/CFS compiled by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), NASEM’s health arm.

For both reports, “it’s really important to base our definition on the best data we can gather,” Chu said. “That’s not just necessarily the scientific literature, that’s also talking to people who have lots of experience personally or professionally.”

For the two long COVID reports, NASEM held public meetings and solicited feedback from people with the disease. The organization’s reports have been “more attentive to patients’ lived experience [in recent years] than they were in the past,” said Paul Volberding, chair of the disability report committee and a professor emeritus at the University of California, San Francisco.

Chu has seen the potential impact of these reports from her experience with the 2015 ME/CFS publication. “It highlighted the symptom of post-exertional malaise,” she said, which was not previously widely used in diagnosing or studying the disease. The 2015 report also “had an impact on treatment,” she said, as it explained how exercise therapy could be harmful to people with ME/CFS.

“The Institute of Medicine report was a game-changing moment for the trajectory of the disease,” agreed Emily Taylor, president of Solve M.E. “There was before that moment, and then there was after that moment.” NASEM’s new long COVID definition report has the potential to be similarly influential, Taylor said, but it must be translated more quickly into government and research policy.

A big tent still leaves some out

Some people with long COVID have lauded the new NASEM reports, particularly the definition report, for describing the challenges they have faced over the last four years.

“After four long years we have a definition for the condition that has robbed so many of us of our health, our relationships and our livelihoods,” wrote Mindy Jackson, a self-described COVID-19 survivor, in an email to The Sick Times. “Finally, we have something that explains, or at least justifies, the myriad of symptoms and diagnoses long-haulers have accumulated after their initial COVID diagnosis.”

But others say the definition report doesn’t do enough to highlight the disease’s most severe consequences, including death. The report “should have mentioned that some of the conditions resulting from long COVID can be lifelong, not just chronic” and that “patients can be bedridden,” Yann Kull, who has severe long COVID, wrote to The Sick Times.

The definition report does discuss deaths from long COVID, citing reports from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that attributed over 5,000 deaths to long COVID based on death certificates. “Long COVID as an underlying or contributing cause of death is likely to be underestimated,” the authors wrote.

However, this potential consequence was not discussed in the report’s summary, press release, or public webinar, leading to limited recognition in media coverage of the report. Similarly, the disability report mentions that some people with severe ME/CFS and long COVID are “bedridden and unable to work,” but press releases and other public discussion have not highlighted this information.

The disability report is also contradictory and dismissive in its portrayal of long COVID in children, said Megan Carmilani, founder of Long COVID Families. “This report does a grave disservice making statements about [the] trajectory of recovery for kids when we don’t know yet,” Carmilani said in a statement.

Still, the NASEM reports are helpful in acknowledging that children can have persistent long COVID symptoms for months or years that “can lead to chronic absenteeism and substantial learning loss,” said Krista Coombs, a long COVID advocate at the Vermont Center for Independent Living.

In addition, neither report mentions that some people develop symptoms similar to long COVID following a COVID-19 vaccination. The definition report describes long COVID an infection-associated condition, which “excludes the ‘long vax’ post-vaccine long-haulers” who experience similar symptoms and functional impairment to people with symptoms following infection, said Sara Johnson, a person with long COVID, in a statement to The Sick Times.

Johnson, like other patient-advocates and researchers, also expressed concern that the NASEM definition may be too broad to support research for people who experience the most severe long COVID symptoms.

This concern reflects a longer debate about defining long COVID as well as ME/CFS. Colleen Steckel, a longtime ME advocate who argues for research and policy to use a more specific definition of that disease, called the new NASEM report “awful,” echoing her criticism of the 2015 IOM ME/CFS report. The NASEM definition will “bury the severe patient group by keeping them out of research” and is “not useful for clinical care,” Steckel said in an email.

On the other hand, broader definitions like NASEM’s can be inclusive of many people and provide an opportunity to look for different subtypes within these complex diseases, said Taylor at Solve M.E. “That’s where the research, I think, should be headed — to look at subtyping by symptom under the umbrella of this definition,” she said, noting that Solve M.E. takes this approach in the research they support.

Todd Davenport, a researcher and physical therapist at the University of the Pacific who studies long COVID and ME/CFS, agreed that the definition invites research into different subtypes of these diseases in a thread on Twitter/X. “Nothing in this necessarily and appropriately broad definition of long COVID would prevent researchers from doing a far better job of identifying relevant phenotypes, using biomarkers, and creating meaningful inclusion/exclusion criteria for studies,” he wrote.

Agencies, institutions, advocates need to take action

While people with long COVID, researchers, and clinicians have eagerly read the new NASEM reports, their original intended audience is government agencies. HHS and SSA commissioned the reports to inform their policies around long COVID; now that the reports have been published, it’s up to these agencies to implement the NASEM committees’ recommendations.

“We really need each agency to rapidly and urgently adopt and implement the definition and put it into practice,” said Bishof, who served on the definition committee. If federal agencies don’t act quickly, people with long COVID will face continued challenges, such as dismissal from healthcare providers and lack of financial support, she said.

The Sick Times reached out to the HHS Office of Long COVID Research and Practice (OLC), the National Institutes of Health Office (NIH) of the Director, the CDC, and the SSA to ask how they plan to implement findings from the new reports. The OLC and NIH both responded with statements saying that these agencies are reviewing NASEM’s findings.

The new working definition differs from prior definitions of long COVID by requiring that people have symptoms for more than three months, said Dr. Tara Schwetz, NIH Deputy Director for Program Coordination, Planning, and Strategic Initiatives, in a statement. “We are still considering how this primary difference might affect research questions,” she said. For example, the new definition may inform inclusion criteria for future clinical trials in the RECOVER initiative, she added.

The disability report was written specifically to inform SSA’s work on long COVID, said Volberding, chair of that report’s author committee. “I’m hoping that they go through it line by line” and closely consider the scientific literature and recommendations, he said. SSA’s press office did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

Bishof emphasized that government agencies need to devote significant resources to education, especially among healthcare providers. “It’ll do something for validation for patients, but if nobody’s taking it seriously or implementing it … then nothing happens,” she said.

How people with long COVID and their allies can use the new reports*

- Bring the working definition report to your healthcare providers, and/or let them know that NASEM has produced a consensus report about this disease.

- Send the reports to your workplace, school, or anywhere else where you may be requesting accommodations due to long COVID.

- Use the disability report to consider whether you may be eligible for disability benefits from the SSA and/or for guidance as you prepare an application.

- Share the reports with your congressional representatives and encourage them to call for the reports to be implemented, through proposed bills and/or initiatives at different federal agencies.

- Share the reports with your state and local government representatives, especially your state and local public health departments, as well as organizations that can help increase awareness of long COVID.

- Use the reports as evidence for any friends or family who are dismissive of long COVID.

*Compiled from advocates who provided comments for this story.

Miles W. Griffis contributed reporting.

This article was published by The Sick Times, a website chronicling the long COVID crisis, on June 18, 2024. It is republished with permission.

Comments

Comments