Plagues are not terribly well known for spawning outbreaks of rationality. And their reputation in 2021, I think we can safely say, is intact. We’d love to believe that in the modern era we have overcome superstition or false panic or misplaced fear, and now “trust science.” But look around you.

We’ve gotten a lot of things wrong over the last year or so, as well as several big things right, and no doubt a whole crew of Captain Hindsights will eventually emerge to pore over the data. Did shutdowns work? Was masking critical? Why the terrible outcomes in South America and now India? How did the U.S. and the U.K., first seen as total losers, come to finish so strong?

But the biggest source of our human errors, it seems to me, is simply our inability to accurately measure risk in uncertain and dynamic situations. I think about this a lot when it comes to mask-wearing, because throughout this epidemic it’s been hard for some of us AIDS survivors not to have some déjà vu.

In some ways, face-masks are the new condoms. They are the critical tools to prevent the spread of a virus; they are not that onerous to use — but they can be inconvenient and irritating. With masks, you lose your face as a way to communicate, you restrict your breathing to some degree, and they’re irritating to put on and off all the time. With condoms, you dull sexual sensation, you put a barrier between you and your partner in a moment of intimacy, you interrupt sex as you fumble with your wing-wang and the rubber, and most men would prefer not to use them.

Using both should be a no-brainer. They largely remove the threat of infection and transmission in an epidemic — even if they are not completely fail-safe. Masked people have gotten COVID-19, though it’s rare; men having safer sex got HIV too sometimes. But the exceptions largely prove the rule. In COVID as well as HIV, as a mysterious new disease spread, there was a debate about the most prudent response — and these two protective products became the center of our attention. There were baskets full of free condoms in the gay bars back then just as there are face-masks available in many stores now, if you don’t have one. They became symbols of safety; and markers of virtue. And our psyches adapted.

Before you jump in, I know the differences between the HIV and COVID are immense. A virus that can be transmitted through the air to many is much more collectively dangerous than one that can only be transmitted by very intimate contact between two people, usually in private. COVID has a case fatality rate of somewhere less than 1 percent, while AIDS for a long time had a CFR of, er, 99 percent. COVID takes up to two weeks to manifest itself in symptoms; HIV can take up to a decade. The authorities swiftly responded to COVID, however haphazardly, while they ignored HIV for a shamefully long time.

But there are real psychological parallels and it’s those that interest me, especially as we look to an end to this awful pestilence. What do we do now as the plague begins to turn into a disease? What precautions do we keep, and which abandon? What is normal any more? And how can we keep rationality in our heads as risks shift?

With the surge of COVID vaccines in the U.S. and U.K. right now, we are in the equivalent period of around 1996-1997 with AIDS, as more and more gay men got on the new drug cocktail. The cocktail wasn’t a vaccine, but it dramatically shifted both death rates and the odds of transmission. Most gay men on these meds saw their viral loads go below any measurable levels. The data at the time suggested that the likelihood of a man with zero viral load infecting another was … zero. In later studies, this was verified. For some, the risk assessment changed completely. For others, not at all.

But with HIV, as with COVID, a transformation of the facts did not necessarily mean a transformation of psychology. Human psyches take time to adjust to new realities; fear and trauma have a habit of outlasting our reason; and stigmas, once imposed, can endure. Camus noted how his citizens in The Plague were oddly resistant to the idea that their pestilence was over, even as the numbers of deaths collapsed. Reactions to the good news were “diverse to the point of incoherence.” But for many, “the terrible months they had lived through had taught them prudence,” or imbued them with “a skepticism so thorough that it was now a second nature.” They had become used to their new routines, and the sense of safety they gave. However bizarre it seems, they became attached to their plague experience.

Andrew Sullivan and his beagle BowieCourtesy of Andrew Sullivan

In this way, gay men became as attached to condoms during AIDS as many of us have to masks during COVID. They remained a reflexive totem of responsibility, a sign of continued vigilance, a virtue-signal to oneself and your partner — long after they made no sense as a way to avoid HIV if you and your partner were already being treated. From those of us with zero viral loads at the start to those today taking the newer PrEP pill that prevents HIV infection, bit by bit, the condom rule has disappeared.

And yet not using a condom for sex — though the overwhelming norm for humans in history — felt weird and scary for a while in the late 1990s, like going into a restaurant without a mask now. Walking my dog in the park mask-free last weekend, I felt the same jitters as when I first stopped using condoms. I felt naked, and a bit daring. But I really had nothing to worry about in either case. I almost certainly couldn’t transmit either HIV or COVID and if I ever somehow got COVID again, it wouldn’t kill me. Just as there is nothing to fear if a few fully vaccinated friends come over for a cozy smoke sesh and chill in 2021, there was nothing rationally to fear in 1997 if two men, fully treated for HIV, had sex without a condom. The moral panic long outlasted its viral reason.

But there are other STIs, the critics claimed! To which the response was: sure, but all treatable and nothing nearly as dangerous as HIV. Today, you hear the same case for using masks indefinitely: look how they effectively prevented flu season last year! To which the answer is: sure, but I didn’t wear a mask for flu season before COVID-19, so why after? The critics insisted: there are variants that could mutate to kill you and others anyway! To which the answer is: so far, very, very little evidence of this. And the more data we get, the better the picture. I remember identical warnings about a mutant “Super-AIDS” ready to pounce once condoms weren’t so common. It never arrived.

The moralizing against those who shifted behavior on purely rational grounds was intense back then — as is the horror at mask-free life is today. A new term was even invented for the activity that had previously been known as sex: “barebacking.” It was an intense word, deriving its power from a whiff of bestiality, the demonization of sodomy and the widespread horror that gay men could be having sex at all in a pandemic. The fear-spreaders made no distinction between those responsibly assessing their zero risk of mutual transmission and equated them with untreated and possibly HIV-positive men who didn’t wear rubbers, and didn’t know or disclose their HIV status. In the same way, we can’t tell the difference between a reasonable, fully COVID-vaccinated person and a reckless one, if you only concentrate on the mask.

Among my COVID PTSD flashbacks to AIDS, I remember wanting to get back to normal in the late 1990s, after my viral load collapsed. I’d been isolated and single for a while because I always disclosed my HIV status on dates only to find my partners swiftly ask for the check, followed by the classic phone fade-out. It was demoralizing and depressing. So I found websites — the old equivalent of the apps — to find other positive men, on which I openly stated my HIV status. I calculated that by only having sex with other positive men who were on meds, I could both be responsible and get a sex life back. There was no risk in these encounters. None. And the HIV disclosure was out of the way beforehand, which was a relief.

But the stigma remained. In fact, a few gay activists who found my racy ad on the site decided to haul me out and publicly shame me for it. They implied I was putting people at risk, when I was actually removing any chance of that. The fact that I was not a lefty was enough of a justification for outing and condemning me; they took sentences of my work out of context to imply I was somehow being a hypocrite; they argued I couldn’t advocate for marriage equality if I was a single slut; and they knew that it was very hard in 2001, when this happened, for me to explain to the general public that “barebacking” was actually rational, responsible, and risk-free, as long as it was with other HIV-positive men on meds.

I mention this because we are in a similar phase in which reasonable people are being irrationally demonized for going back to normal and going mask-free. It makes no sense, but the truth is we get attached to rituals of safety, even after they have become redundant. Look at airport TSA screening, twenty years after 9/11. We so identify with safety protocols that it can feel dangerous simply to follow reason when circumstances change. The fear of COVID somehow gets internalized and perpetuated, just as HIV was. Even today, for example, a diagnosis of HIV feels far more terrifying than, say, diabetes. But diabetes is much, much more problematic now than AIDS, over a lifetime. COVID now seems much scarier than the flu. But if you’ve been vaccinated, that’s exactly how we should think of it. Nasty, but not fatal. So live!

It is true that COVID is not over; that we should not totally relax; that many who refuse vaccines could be a problem; that mutations matter. For what it’s worth I have nothing personal against masks. I wore them from early February of last year and was punctilious about them. But the situation has changed, and as more and more get vaccinated, and the human “herd” of the vaccinated grows larger, the odds of infection will decline. Bottom line: this viral motherfucker is on the ropes and we do not need to be in a state of permanent terror.

Should we publicly mask to “help contribute to a culture of mask wearing”? I see the point. Wearing a mask is so much more public than wearing a condom, and we can role model. But there’s a cost to this too: if people see no-one being liberated by the vaccine, they’ll be less likely to get one. And if leaving masks behind is the fruit of vaccination, the more people in the party the more will want to join.

In that respect, I have no problem with some indoor spaces — bars, restaurants, hotels — requiring proof of vaccination to get in. We need the attraction of going back to normal life to incentivize vaccination, and fear can actually hurt that. People need positive as well as negative motivation. In exactly the same way, those who want to continue wearing masks can … continue to wear masks. I’m pretty sure I’ll be wearing one in trains and planes forever from now on. The mask-wearers may well have healthier lives if they do, just as regular condom wearers avoid all STIs. But it’s not some kind of moral achievement. It’s just a choice we no longer have to make.

So get vaccinated. Then use reason. The point is to get back to normal life, not to perpetuate the damaging patterns of plague life. So take off your masks, if you want. Plan parties for vaccinated friends. Get your vacation plans ready. And stop the constant judging and moralizing of people with masks and those without. Summer is coming. Let’s celebrate it.

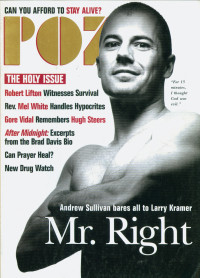

Andrew Sullivan is a self-described “recovering blogger” and a long-term survivor of HIV. To read the 1997 POZ cover story about him written by Larry Kramer, click here. To read the 1995 POZ cover story about Larry Kramer written by Sullivan, click here. Sullivan’s current gig is The Weekly Dish. This opinion was originally published on The Weekly Dish. For more information on The Weekly Dish and to sign up, click here.

2 Comments

2 Comments