Like a specter, death haunts the more than 150,000 people age 55 and older who are currently incarcerated in the United States. These individuals live under the burden of institutionalized inequities that frequently generate a multitude of preventable medical problems as well as the health complications that inevitably accompany growing old in prison.

Five years ago, I met Alejo Rodriguez, one of these individuals. I’d been invited to visit the all-male Otisville Correctional Facility to speak at the institution’s World HIV/AIDS Day event. The former municipal sanatorium was originally built to house patients suffering from the highly contagious disease tuberculosis in a setting less populous than the teeming and congested streets of New York City. The town of Mount Hope in the mountainous rural area of upstate New York’s Orange County provided both the controlled isolation patients needed to recover and the benefit of fresh air in a tranquil environment. It remained a hospital until the doors closed in 1955.

In 1977, the establishment was reincarnated as a place of confinement for men convicted of crimes. Surrounded by a fence topped with wicked-looking razor wire, the facility sprawls beneath the gray gaze of a hulking mountain. Upon approach, the medium-security prison could easily be mistaken for a concentration camp. That perception is reinforced when, after a mandatory stop at a little border-crossing-style security checkpoint, an officer checks your identification before waving you through.

My address to the men was casual and unscripted. As I looked out at the crowd from behind the rostrum where I stood, I perceived a sea of hoary, haggard faces that returned my mildly questioning gaze. One thought predominated: These men all looked so old.

Later, during a break in the program for lunch, I spoke to some of the men. Most, like Rodriguez, were friendly and chatty. Asked to stay, I agreed to speak at a second session. Amazingly, the auditorium was full. This was heavy-duty stuff for a bookish editor more comfortable doing research online than finding the right words to convey a message of health and hope to men I thought probably had seen and done it all.

Now, once again, we sat talking. This time, however, he was a free man, the arts and civic engagement coordinator at Exodus Transitional Community, a reentry organization in New York City’s East Harlem. Clad in jeans and a long-sleeved mock turtleneck the color of a shiny new penny, his head was shaved smooth. He still looked boyish; the only feature that hinted at his advanced years was the silvery stubble precisely shadowing his face. In the airy, light-washed central conference room on the second floor of the agency’s new building, he seemed relaxed and reflective.

Alejo Rodriguez is now the arts and civic engagement coordinator at Exodus Transitional Community, a re-entry agency, in New York City’s East Harlem.Kate Ferguson

“When I first went to Otisville, it was already being dubbed the ‘retirement home for lifers’ among men throughout the state,” Rodriguez says with an easy smile. “One gentleman called it the ‘elephant graveyard for lifers,’ and I said, ‘Get me the hell out of here!’”

Arrested in 1985 for a robbery-related homicide, Rodriguez—born and bred in the Bronx— spent 32 years of his life sentence in New York state correctional facilities located throughout different regions of the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision prison systems.

“Generally, they begin the process [of where to house you] by sending you up to the northern facilities, such as Clinton, Attica, Wende or any one of the maximums farthest north. That’s where they examine how you’re going to behave,” he explains. “If you’re not problematic, then they allow you to migrate back down closer if you’re from New York City.”

Like many men in prison, Rodriguez dedicated some of his time behind bars to self-transformation. His journey took him through those prisons located in an area of upstate New York dubbed the “North Country” by some historians. His odyssey ended in Otisville, where frequent periods of reflection resulted in self-improvement that caused him to marvel at the changes he experienced in his mental, physical and spiritual outlook. He devoured the “stereotypical books read by so many men in prison seeking personal insights—The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Invisible Man, Native Son, Down These Mean Streets and Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave—all autobiographies,” he says. “I started realizing that other people had struggled with similar issues in their lives, whether it was racism or just trying to be a man.”

Through literature, Rodriguez reached for growth. Gradually, reading the words of others unlocked his own desire to be heard. “First, it started out with poetry, and then I began writing more in depth,” he says. “I wanted to connect with people and yearned more for the desire to belong. But I realized the position I was in. Where I was at wasn’t a place that supported growth. I think that was the thing that I was most afraid of being in prison, that in there, my mind, my sense of purpose and my sense of who I am as a person couldn’t grow anymore, and so I sought out ways in which I could grow.”

That epiphany propelled Rodriguez to chase his dream to attain higher education. “I spent three years in Auburn, a total of 14 years in Eastern, a year in Sing Sing, then six in Arthur Kill and another six in Otisville,” he says. “Initially, I got transferred because they did have college programs back then when I first came into the system.”

Rodriguez moved through the system strategically and purposefully, migrating to facilities where he could take advantage of college courses. “I got my associate’s degree when I was in Attica, and I heard at that time that Syracuse University was in Auburn Correctional Facility, so I went to Auburn,” he explains. “And I went to Sing Sing because SUNY [State University of New York] New Paltz had a master’s degree program there. But it was about that time that they started shutting down the college programs.”

In hindsight, Rodriguez’s moves proved to be smart. Evidence supports education as a way to reduce recidivism, improve economic opportunities for those serving time and help formerly incarcerated individuals successfully transition back into their communities. Practical obstacles, however, such as limited funding and lack of access to financial aid, stare down the men and women in prison who hunger for learning and wish to better themselves and their circumstances in every way.

As Margaret diZerega and Ruth Delaney of the Vera Institute of Justice’s Center on Sentencing and Corrections observed in findings on the state of financial aid for incarcerated students, when these barriers were lifted, colleges were as quick to create programs for this population group as folks in prison were to step up to enroll. The U.S. Department of Education’s Second Chance Pell Experimental Sites Initiative, which temporarily reinstated the eligibility of incarcerated people to apply for higher education grants, certainly confirmed this in California in 2014, when such college programs boomed.

Rodriguez was and is a believer. By 2003, when he was first up for parole—at age 41—he’d been incarcerated almost 20 years, and he’d accomplished plenty. “I had a master’s degree, was a published poet with my work featured within several books and had been involved with several additional programs that were more than what was required,” he says. “I got denied.”

The parole board said this was because of “the ‘nature of his crime,’” Rodriguez says. Then they delivered a kick to his gut.

“They said the sentence the judge gave me wasn’t enough,” he says. “I had gotten sentenced to less than the maximum—I could have been given 25 to life—but they gave me 18 to life.”

Following standard practice, Rodriguez returned to see the board every two years after that. A total of 10 appearances and 10 denials followed. Along the way, he filed the requisite appeals. “I had gotten several reversals where the judges said they couldn’t understand why I was still being denied parole,” he says. “They’d send me back, and the parole board just denied me all over again, repeating ‘nature of the crime’ and adding on another reason, ‘lack of insight,’ which even they couldn’t define. I’d get another reversal, go back, and then we’d start the whole process all over again.”

Finally, in 2017, on his 11th try, Rodriguez made the cut, a full 14 years past his minimum.

When he returned home, Rodriguez took advantage of an opportunity to work at the Prisoner Re-entry Institute. The organization is one of 12 that make up the Research Consortium of the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. For him, the job offered growth in new directions, including a chance to help “rekindle my humanity and develop working relationships with sisters in the workplace,” he says.

“I didn’t know how to even describe that prior to me experiencing it,” he observes. “I was thinking I’m free; I’m out. As far as women, I was thinking just in terms of black and white because I’d been deprived of sex for 26 years. And then I realized that there was so much more in between, such as relationships, having women as friends, talking and just sharing conversations. I just had to get reacclimated into that. I realized how much I’d missed in that way, not because of the years, but because of losing so much of my humanity.”

“Do you remember Chas?” Rodriguez asks me. For a moment, I draw a blank. Then he offers a prompt. “Charles, you know, he was at Otisville when you were there; he was the emcee for the program.” A nut-brown face belonging to a bluff and dynamic force of a man who shook my hand and escorted me up the stairs to the stage floats through my mind, remaining present long enough for me to recall.

“He died of an apparent heart attack; he was paroled just after me,” Rodriguez says. “He wasn’t even out three months.”

Three years before Rodriguez was released, in the spring of 2014, I spoke with Mujahid Farid, who was 64 at that time. Four years later, he died too, succumbing to pancreatic cancer seven years after he was released in 2011, having served 33 years. In 2013, Farid cofounded the grassroots organization Release Aging People in Prison (RAPP).

Mujahid Farid, co-founder of the Release Aging People in Prison (RAPP) campaignKate Ferguson

In the spring of 2015 when I talked with him, he was preparing for a symposium in partnership with Columbia University’s Justice Initiative, the Correctional Association of New York, the Osborne Association, the Be the Evidence Project and the Florence V. Burden Foundation.

The meeting, which drew some of the most outstanding thinkers in the social justice field, produced a series of papers that provided a rich and varied overview and analysis of the aging prison population.

Today, even more people—academic researchers, health care experts, activists and advocates for social justice, law enforcement officials and other key stakeholders—are discussing mass incarceration, sentencing and parole reform, and the rising number of elderly individuals in prison as matters of public health that require immediate action.

In an expansive article about findings from a national survey on parole board requirements conducted by the University of Minnesota’s Robina Institute of Criminal Law and Criminal Justice, authors Jason P. Robey and Edward E. Rhine clarified data showing that, in their words, “criticisms of the statutory requirements for [parole board] membership are not unfounded.” They continued, “The rigor and range of statutorily required qualifications for releasing authority members varies significantly across the country.”

Many states reported having no such qualifications, and even those with statutory requirements for board members possessed markedly different expectations governing protocols for appointment, resulting in great variety from state to state.

Jose Saldaña, the director of RAPP, whom Farid appointed to carry on the group’s work, well understands not only the arbitrary nature of these variables but also the painful toll these undetermined factors can take on individuals, families and communities.

Jose Saldaña, director of RAPPCourtesy of RAPP

As a young man of 27, Saldaña was arrested, charged and convicted of the attempted murder of a police officer. (A trial found that he never fired the weapon that almost killed the policeman.)

Saldaña’s wife, Rosa, worked for RAPP in the early stages of the organization’s development and introduced him to Farid. The two had plenty in common, as they learned after they began talking with each other Saldaña realized that Farid’s conversations on the outside were about exactly the same issues that he and others in prison were discussing as they tried to figure out a way to deal with the current system of punishment.

“Farid knew better than most and understood perfectly well that the process of parole went beyond a crapshoot and a roll of the dice because the dice are loaded,” he says. “We knew that we had to focus on the composition of the parole board.”

Mark Shervington, a community organizer for RAPP, was also formerly incarcerated. He recalls that when he was up for parole—10 times in total—“the board was composed of people with primarily law enforcement or prosecutorial backgrounds,” he says. “There were no individuals with a background that would qualify or enable them to sit in evaluation of people as human beings with the capacity for change.”

In 1986, Shervington, a native of Queens, New York, went to prison for shooting and killing the man who sexually assaulted his fiancée. “That’s how I got there,” he says. “But along the way, I wasn’t just lifting weights and playing basketball. I spent a lot of time in various self-help programs and did more than what was expected and required of me in the way of how I would do my time.”

Mark Shervington, community organizer at RAPPCourtesy of RAPP

Nevertheless, board members immediately and consistently refocused on the circumstances that cost Shervington his freedom, discounting his efforts and accomplishments while behind bars. Each time he was denied, “it would seem like I was back in front of the judge being sentenced again [for the crime] because that was the tone and the language they used,” he says.

“I felt like my record and my activities demonstrated that what had happened was at that moment in time, and I had proven that I didn’t think or act like that now,” he says. “But up to that point, the people on the board were these lock-’em-up-and-throw-away-the-key types who couldn’t see past that.”

By the time he was eligible for parole a 10th time, Shervington says, with a derisive snort and uncomprehending shake of his head, “I had done everything except walk on water.”

Shervington is grateful that he survived to get out, especially because he entered prison a relatively healthy young man and left with a broken heart. “Literally,” he says.

Near to his 50th birthday, Shervington felt unwell and thought he’d contracted the flu from someone. In addition, he was sure that preparing for another appearance before the parole board had caused him undue stress. “I thought I had it under control, but out of nowhere, this thing comes and knocks me on my behind,” he says.

The doctor told Shervington that he might have had a myocardial infarction, he says. “I didn’t know what he meant, and he never explained it to me in just plain English, even after I asked him what that meant. He just repeated it—didn’t offer me an aspirin or anything. They took an EKG, and he based his statement on that. Then it happened again, so I got a little scared because I didn’t know what’s going on.”

Shortly after this episode, Shervington was finally granted parole. “When I got home, I went to St. Luke’s to see a real doctor, and I explained the situation I had just left and what had happened to me,” he says. “So she checked me, asked me a few more questions, then looked me dead in the eye and said, ‘You had a heart attack!’”

“She put me on aspirin, sent me to the cardiologist and put me on track to get the problem repaired,” Shervington says. “I didn’t know that the heart attack had actually burst a valve in my heart. It was like I was bleeding to death on the inside.”

Saldaña says he and his associates in prison watched as other men around them—“people in their late 50s, early 60s”—died. An old-timer he met gave him a Koran and a medical dictionary.

“This guy was in perfect health, but he passed away because over the years jail just took its toll on him,” Saldaña says.

“I realized that I had to take care of my own health; prevention was everything to me,” he continues. “And I had to be able to read a lab report, read symptoms and seek medical attention whenever I thought something was happening with me. I’d have my wife get me updated medical dictionaries and ask her questions about different issues, and we stayed in tune with my health. That meant the world to me because as other people were passing away from medical neglect, at least I was on top of everything. But still, bottom line, you don’t control when you die in there,” he adds.

Saldaña’s experience with the parole board didn’t match Shervington’s exactly. He was denied parole four times. “For me, the most difficult part was having to tell my family that I’d been denied again and again because they don’t actually see the system of punishment the way we see it because we’re living it,” he says. “My family has been part of my transformation; they’ve helped me prepare my parole packages, so they’ve seen what I was presenting, and they were just convinced that I had to get released. The way they viewed it was that someone who had accomplished the things that I had accomplished should get released; that was unquestionable to them.”

“The High Costs of Low Risk: The Crisis of America’s Aging Prison Population,” a white paper prepared by the Osborne Association, an organization committed to transforming the criminal justice system on multiple levels, called the broader mechanisms driving parole “remarkably nebulous.”

Zeroing in on key aspects of the problem, the association emphasizes, “Members of the Parole Board are not elected but appointed by state governors, and there is no clear system of checks and balances to ensure a fair appraisal of parole applications. Incarcerated individuals may put in tremendous effort to transform their lives by completing programming, earning advanced degrees, and becoming assets to society, only to see their application denied solely on the basis of ‘the nature of the crime’—the lone factor that can never be changed and speaks only to past circumstances rather than who a person has become.”

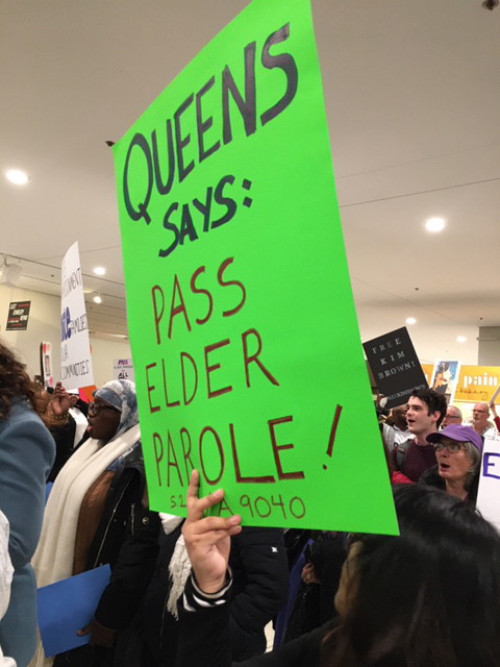

Most parole boards operate under state laws, regulations and guidelines that allow its members to use their discretion to make decisions about the character, behavior, rehabilitative efforts and achievements, and overall readiness of individuals who come before them to be assessed for release. In New York, the state legislature has sponsored two bills—the Fair and Timely Parole Act, which would make it hard to deny individuals parole based on the type of crime committed, and an elder parole bill that would render individuals over age 55 who have served at least 15 years in prison eligible to apply for parole regardless of their sentence.

Community advocates and supporters mobilize to rally, march and meet with legislators on behalf of elder parole at a “Day of Action” event at the New York State capitol in Albany, New York.Kate Ferguson

Democratic State Senator Gustavo Rivera elaborated on his sponsorship of the Fair and Timely Parole Act in an op-ed in the Daily News. “The bill requires that the Parole Board give incarcerated people a thorough and individualized evaluation not solely based on the nature of their crime,” he wrote. “The bill would change state law to ensure decisions are based on who people are today rather than who they were years or decades ago.”

Saldaña says he and other people of color begin life with “a lot of historical events that led to our predicament” and “certain social and economic conditions we inherited.” But by their actions and accomplishments, people have shown that reform and rehabilitation are possible. “We felt that it was our responsibility to change those conditions, as opposed to being subjugated by them,” he says. “As men growing up in the ghettos of New York City, we felt that we had no excuse. We had pioneers before us who paved the way, and we just didn’t pick up the torch.”

Now, Saldaña is one of the leaders of the charge. Parole boards need to release elderly “men who are languishing in prison with college degrees who have been instrumental in transforming whole generations of younger men in the last 30 to 40 years,” he says. His voice is tinged with just a hint of weariness as he asks, “Do these men deserve a second chance? Do they deserve to return and reconnect with their grandkids and the kids they left behind who grew up without them?”

Fueled by the accelerated aging of incarcerated individuals 55 and older, the growth of the geriatric prison population has been a crisis in the making since the early-1990s. As mounting scientific evidence has started to confirm, incarcerated people tend to develop chronic illnesses and disabilities at a younger age than the general U.S. population, a direct consequence of life in prison.

Driven by judicial legislation that boosted the length of sentences prosecutors could recommend for violent felonies and drug-related crimes, a steady increase in mandatory minimum sentencing laws, multiple-strike statutes and a decrease in the number of people eligible for parole, institutions became teeming cities filled with an increasingly aged and infirm populace.

End of Part 1 of a two-part series on aging in prison. Click here to read part 2.

This article was written with the support of a journalism fellowship from the Gerontological Society of America, Journalists Network on Generations and The Commonwealth Fund.

1 Comment

1 Comment